The place-name Stanhope comes from two Old English elements, ‘stan’ or stone, and ‘hop’ or side valley, thus it means the ‘stone side-valley’ (1). The name was originally applied to the valley of the Stanhope Burn (sometimes written as two words, sometimes as one, as in Stanhopeburn) which enters the river Wear at this point, but then became transferred to the settlement which grew up at the junction. The place-name Stanhope is first mentioned about 1170 in a charter relating to the family of Bishop Hugh de Puiset. Stanhope Park occurs in many medieval documents as one of the Bishop of Durham’s hunting preserves.

The ecclesiastical parish of Stanhope formed the western portion of the Manor of Wolsingham. Stanhope’s parish church of St. Thomas has Norman origins (2). By 1421 Stanhope had developed into a market town, about half-way between Durham City and Alston in Cumberland, with a market place along that main road, or Front Street, serving the growing population of the hinterland which was attracted to work in the local lead mines. As the major landowner of the High Forest of Weardale was the Bishop of Durham, he also owned the rights to mine lead there (3).

The importance and prosperity of the area led to several large buildings being constructed nearby in the late-medieval period, also in the 17th century and in Georgian times. Examples include the late-medieval Stanhope Hall a short distance to the west of the centre, the 17th century and perhaps earlier Unthank Hall across the river, and Stanhope ‘Castle’, built in 1798 in the style of a romantic castle and enlarged in Victorian times to give hospitality to shooting parties. Grand accommodation for past rectors is also a feature of Stanhope, with Stone Houses in Back lane having served as the rectory until 1697, when it was replaced by the Old Rectory on Front Street.

Due to the erratic pattern of employment in lead-mining, and also the hazardous nature of working in the industry, both of which could lead to a miner’s wife and children becoming dependent on poor relief, provision for the poor was a particular concern in Stanhope parish. A survey of 1797 gave the population as stable at 3,600, but only about 80 members belonged to the two Friendly Societies. The Poor House had been built about 1782, and the operation of the Poor Law system had been ‘farmed’ out to contractors, with a result which was not totally satisfactory as demand was increasing, costs were rising, and quality of provision declining. The contractor was therefore providing a poorer diet than the ‘bill of fare’ which he was supposed to provide. The influence exerted by the Quakers on the Stanhope area meant that a fairly strict line was taken with those who were fit but work-shy. In 1797 there were said to be 22 poor people actually in the Poor House, with another 100 families receiving weekly out-relief. Most of the population were said to be Church of England, but there was one congregation of Methodists and another of Presbyterians (4).

A word picture of Stanhope in 1848 is provided by Slater’s Directory (5) of 1848. It describes Stanhope as being situated in a mountainous district supplying great quantities of lead ore and lime, (agricultural improvement at that time creating a high demand for lime). The benefice of the church was said to be in the gift of the Crown and the Bishop of Durham alternately. The Methodists had a chapel and a Sunday School at Stanhope. A National School had been established by Bishop Barrington, one-time Rector of Stanhope, and there was also the Hartwell Endowed School founded in 1724. Stanhope also had a savings bank and a subscription library, and the 76 commercial entries show a wide variety of tradesmen including blacksmiths, shoemakers, butchers, cartwrights, joiners, stonemasons, surgeons, tailors, and even an animal and bird preserver, as well as 5 public houses. In addition to the lead mines, local employment also depended on the large works of the Weardale Iron Company. Rail communications mentioned included the line from the lime and iron works to Shields, and the Wear Valley Railway which had reached Frosterley, two miles away to the east, and which it was hoped eventually to extend as far west as St. John’s Chapel. The Wear Valley Railway was built to export the Weardale minerals of coal and limestone to the rest of the country via the port of Stockton-on-Tees. The line had reached Frosterley in 1847 from the Wear Valley Junction, which connected with Shildon and then Darlington (6).

Another picture of Stanhope at a similar period is provided by the 1st edition of the 6 inch Ordnance Survey map published in 1857. The village is shown flanking Front Street with, from the east, a ‘terminus’ of what would become the Wear Valley Railway, the Queens Head Inn, The Rectory and, up East Lane towards Newfield, the then Workhouse. Set back from the main road to the north on Back Lane are Boxwood Hall, the Barrington Endowed School, Stone House (the pre-1697 rectory) and Woodbine Cottage, along with St. Thomas’s Church, also the then Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. The Town Hall of the day is shown at the junction of the main road and Back Lane. A short distance further west, at right angles to the main road, is Emma Street. On the south side of the main street, extending down to the river bank, is Stanhope Castle and its associated Castle Park. Further west, across the bridge crossing the Stanhopeburn which is probably of medieval date and was widened in 1792 (7), is Stanhope Hall, a building of some antiquity.

From just east of the bridge is a road leading north, past the area called Ashes, to Lanehead, the name coming from its being the head of the turnpike road, with a gate and tollhouse. In this area is an industrial complex which includes the Stanhopeburn Iron Works, quarries, limekilns, and the terminus of the railway which connected Stanhope to South Shields and ran up Wasterley, named somewhat confusingly as the Stanhope and Carrhouse Branch of the Wear Valley Railway. The line is shown running through the hamlet of Crawley, with its Cambridge Arms public house, and just north of Crawley was sited the Crawley Engine to provide haulage power. Up in the valley of the Stanhopeburn was an area of lead working. As well as various Old Shafts, and Levels, was Stanhope Lead Smelting Mill with tunnel chimney, a crushing mill, Stanhopeburn Washing, an engine house and a waggonway down to the Lanehead railway terminus.

Evidence of changes which occurred later in the 19th century can be found in Kelly’s Directory of 1879 (8). Stanhope Church had been restored in 1868 under the direction of the London architect Ewan Christian. The National School endowed by Bishop Barrington had been built (or rebuilt?) in the Elizabethan style and comprised excellent classrooms for boys, girls and infants, plus a master’s house. A ‘commodious’ building for concerts and lectures, with a good reading room, had been erected in 1867, and in 1879 Stanhope had gas lighting and an excellent public water supply. The number of directory entries had grown to 97, and included two banks, the gas light company, co-operative store, a seedsman and 8 public houses. Despite the optimism of a few years earlier, Stanhope was still the terminus of the Wear Valley railway. Stanhope’s trade was still based on iron and lead mines and limestone quarries, and coal is also mentioned.

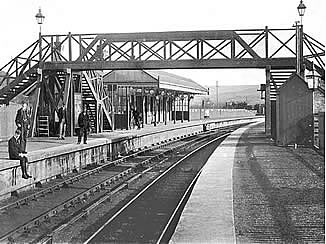

The 2nd edition of the Ordnance Survey map of 1898 shows several significant changes. The main road has become part of the St. John’s Chapel to Wolsingham turnpike road, and the Wear Valley Branch of the North Eastern Railway had been built running up the Wear Valley, with a station near the old terminus. A new station had to be built because the old one proved to be in the wrong place (9). The new line has led to more development along Front Street. A new Weardale Union Workhouse had been built east of East Lane, with other development around East Lane. The National School had been rebuilt, and also on Back Lane was another school near the Methodist Chapel. A smithy and another Methodist Chapel had been built near Emma Street, also West End Terrace.

Up at Lane Head, the Stanhope Burn Iron Works has become disused, Lanehead Quarry had also become disused, as had the Stanhope Smelting Mill, but the flues leading from this had been extended since the time of the 1st edition map. The Stanhope and Carrhouse branch railway, now marked as leading to Edmondbyers, was not only functioning, with the Crawley Engine still marked, but had been extended southward as a mineral line into new areas of quarrying between Ashes and Stanhope.

Early in the 1920s there was a 3rd edition of the O.S. map almost exactly contemporary with a directory. The 1923 map shows these quarries to have been considerably extended eastwards, east of East Lane, into Newfield Quarry, the mineral railway also having been extended. Edward Street is shown as having been built next to Emma Street, and some more development has taken place around West End Terrace and New Town. Near Ashes, the Hope Lead Level has been opened. Kelly’s Directory of 1925 (10) mentions that the Primitive Methodist Chapel, which had been built in 1876, could seat 700, as could the Wesleyan Chapel which had been built in 1870 and enlarged in 1891. The Town Hall, a stone building with a large hall used for public meetings, had been built in 1901 - perhaps begun 1901 and completed 1903, the architects being Clarke and Moscrop of Darlington (11) - and there was also a reading room and library in the town. The Durham County Consumption Sanatorium had been established in 1899 and had 45 beds reserved for men only, and the parish housed the Wear Valley Beagles. Stanhope Dene had been laid out at the west end of the town during the Durham coal strike in 1891, and consisted of 2 miles of pleasantly wooded walks with seats, a bandstand, and a stream crossed by rustic bridges. The trade was still dependent on Weardale’s iron and lead mines, and the numerous limestone quarries in the area. By 1938 (12) the number of directory entries had grown to 165.

Mining History

The development of the lead-mining industry in the Stanhope area was in no small measure due to the involvement of the bishops of Durham. Even in medieval times they brought to bear on it a sophisticated level of commercial organisation. Being educated men, and having administrative employees to implement the organisation, their ownership had advantages denied many other mine-owners. Furthermore, the bishops’ well-kept archives have preserved documents which give detailed pictures of their lead-mining activities (13). Successive bishops worked their Weardale lead mines either directly through agents, or by leasing them to others, in which case the bishop retained one-ninth of the ore won, known as the Bishop’s lot ore. The Rector of Stanhope included within his tithe entitlement a tenth of the lead production after the Bishop’s ninth had been deducted (14). This lead tithe so inflated the Rector’s income that it made Stanhope one of the richest livings in England, particularly during the 18th century when lead production was high (15), and so becoming Rector of Stanhope was considered a highly desirable appointment.

In the late 17th century, mines were leased to two companies which were to feature prominently in the history of Weardale lead mining, the London Lead Company, often called the Quaker Company, which had been founded in 1692, and the Blackett-Beaumont Company begun by Sir William Blackett in 1684 (16). This latter Company subscribed to the National School in Stanhope.

Lead was transported from the Weardale mines by an early railway, the Stanhope and Tyne line, a composite of inclined planes with stationary engines and conventional locomotives which carried the lead to Tyne Dock at South Shields (17). The 1853 6 inch Ordnance Survey map shows the terminus of the line, described as the Stanhope and Carrhouse Branch of the Wear Valley Railway. The line runs south to the industrial complex at Crawley. Nearby was sited the Crawley Engine which provided haulage power.

The valley of the Stanhopeburn was one of the main areas of lead working. As well as various Old Shafts, and Levels, the 1853 map shows Stanhope Lead Smelting Mill with tunnel flue, a crushing mill, Stanhopeburn Washing, an engine house and a waggonway down to the Lanehead railway terminus. The Stanhope Smelting Mill had become disused by the time of the 1898 map, but its flues had been extended since the 1853 map. The 1898 maps shows the Stanhope and Carrhouse branch railway, now marked as leading to Edmondbyers, still with the Crawley Engine, but the line had been extended southward into new areas of quarrying between Ashes and Stanhope.

|